Photography and Prints

Title: LET'S GIVE HIM ENOUGH AND ON TIME

NORMAN ROCKWELL (1894-1978) LET'S GIVE HIM ENOUGH AND ON TIME. 1942. 28 1/2x40 inches, 72 1/2x101 1/2 cm. U.S. Government Printing Office, [Washington D.C.] Condition A-: sharp vertical and horizontal folds; creases in margins and image; minor tears and losses at edges. Paper.

Title: Manos

Print #89 of the edition of 100. Cream wove paper. The full sheet. Fine impression. Fine condition. Provenance: Taller Jesusa, Mexico City, Mexico. In addition to Friedeberg, the Jesusa atelier has edited and published works by Tamayo, Goeritz, Felguerez, and Arturo Rivera, among others. He was not raised Jewish but rather atheist. Once a servant took him in secret to a church to be baptized. He says because of this and other experiences, he has seven religions, one for each day of the week. Friedeberg consults the I-Ching everyday and has a collection of saints. His biography on the Internet includes a passage that reads “I get up at the crack of noon and, after watering my pirañas, I breakfast off things Corinthian. Later in the day I partake in an Ionic lunch followed by a Doric nap. On Tuesdays I sketch a volute or two, and perhaps a pediment, if the mood overtakes me. Wednesday I have set aside for anti-meditation. On Thursdays I usually relax whereas on Friday I write autobiographies." He says that the world lacks eccentrics today because people have returned to being sheep through the consumer culture and television, which wants us all to be the same.

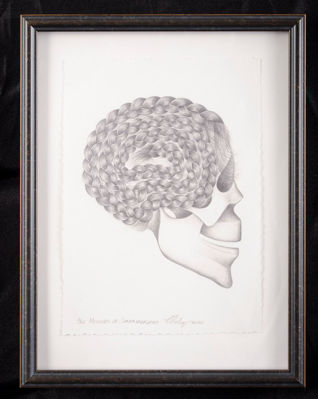

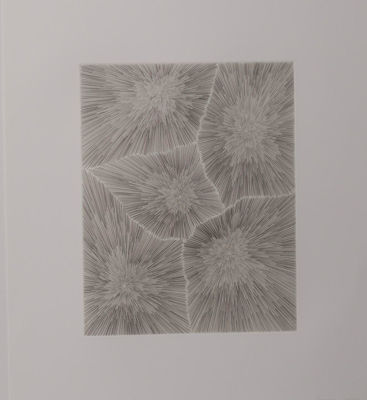

Title: Marcel

Sakura explores personality through a merging of abstract or non-human elements with the recognisable traits and shapes of a portrait — using the willingness of the viewers brain to find a face from an unsuspecting origin. “Marcel” finds that human aspect in the subtlest denomination, the illusion of face projected through a hazy build up of spheres in a cloud-like sub-summation — the shapes carefully arranged to delicately suggest features and muscles in a use of positive and negative space. A set of six forms of unknown calibre (but reminiscent of organic cells, particularly sperm, or sheaths of wheat, or finger-like protrusions) penetrate into or out of the mass and suggest a violent and possibly sexualised combination. The work is afforded such a fine detail through the artists combined use of intaglio and chine-collé printing process, each allowing a very fine control of line, and the junction allows a textural variation and added depth between the base figure and the swarming cell-like entities.

Title: Marilyse

Wild, alien form by Sakura, whose work over the last two decades with intaglio printing has conjured onto paper a variety of strange and fascinating creatures. Large eyeballs on thin limbs extend over a single, encompassing mouth — the oversized elements and dual, dripping uvulas adding a sexualised tone that is subtly reinforced by Sakura’s common usage of female names (this is “Marilyse”) for his work.

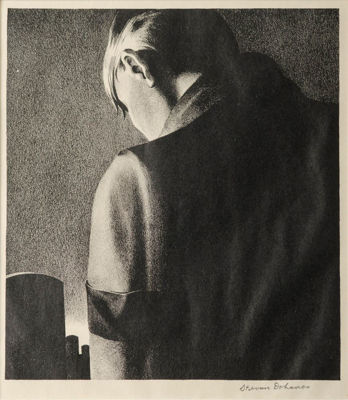

Title: Mural Study-Triborough Bridge

Lozowick is renowned for his Precisionist style with his lithographs, influenced in part from his travels through Berlin and Moscow and associations with styles such as Russian Constructivism, Bauhaus, Futurism and De Stijl, and contact with artists such as El Lissitsky. The sharp, geometrically inclined murals focus heavily on the repeating forms and patterns of mechanised industry and the urban environment, but convey humanist principles and an ultimately optimistic view of industrial progression and the human condition within 1930s New York.

Title: Nautilus 10548

This advertising poster for General Dynamics is part of Nitsche’s series from 1955 celebrating “Atoms for Peace”. This particular poster depicts the first atomic powered submarine coming out of a Nautilus shell. portraying it as a part of a natural technological progression. This series is very much a product of the Cold War. Each poster represents a peaceful use of the atom in response to the public’s fear of this dangerous new technology. The style is intended to reinforce a vision of a clean, peaceful, technocratic, atomic future that never quite arrived.

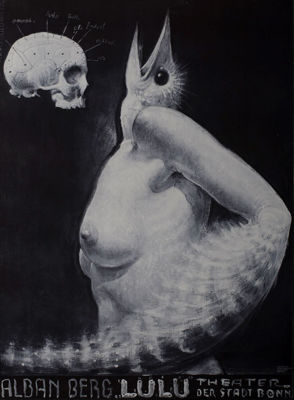

Title: Owl

Baskin forms a narrative that cycles around subjective constants: local and ancient mythologies, animal and figural depiction, folk-like engendering and interpretation. The owl of this woodcut finds a gnarled, elongated form from the artist’s hand, a depth of focus put into the roots and curls of the talons, whilst the prevalent wise wide eyes—and the entirety of the head itself—are almost entirely obscured in an impressionist flurry of stroke and feather. Original done for Anne Ratner Fern 453